Federal emergency management began in 1803 with federal appropriations passed to aid Portsmouth, New Hampshire with rebuilding after a devastating fire destroyed much of the town in late December 1802. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), between 1803 and 1950, Congress passed 128 separate laws to deal with disaster relief. However, after the Second World War, there was a significant policy shift toward a standing federal disaster relief program. In 1950, Congress passed the Federal Disaster Relief Act which authorized the President to provide federal assistance when prompted to by governors. Later, in 1968, Congress passed the National Flood Insurance Act, creating the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). During the 1970s, several large disasters caused the federal emergency management strategy to continue to change, including the creation of FEMA under the Carter Administration. In 1988, the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Act was enacted, authorizing most of FEMA’s disaster response activities.

The Disaster Relief Fund (DRF), managed by FEMA, is a crucial component of the federal government’s current general disaster relief programs. These programs are activated when local and state capacities are exceeded and are rooted in the Stafford Act. The DRF has grown substantially over time, reflecting an increasing federal involvement in disaster response.

DRF funds are allocated for a range of activities, most significantly those following a major disaster declaration, including Individual Assistance, Public Assistance, and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program. Other uses include pre-declaration activities, emergency declaration responses, assistance for managing wildfires, and ongoing disaster readiness and support. Understanding the evolution of the DRF and federal disaster relief policy is critical for Congress when contemplating future emergency management and budgetary strategies.

Funding History

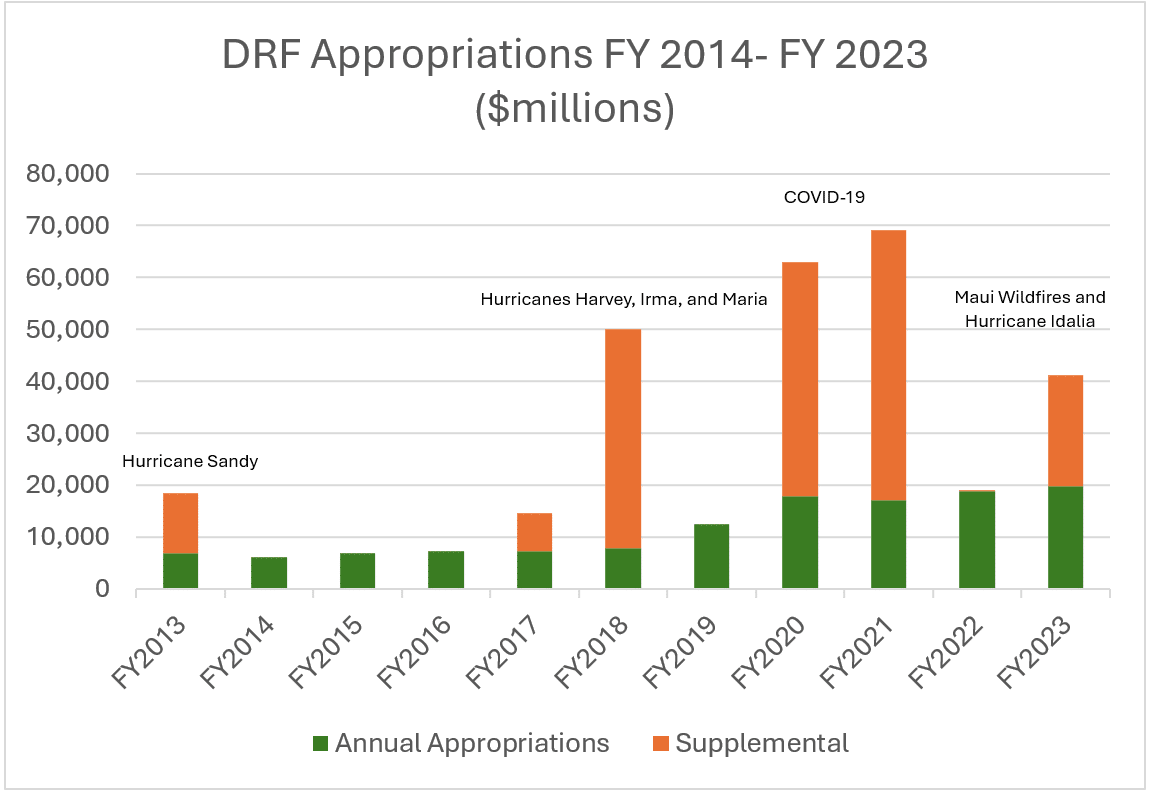

The history of DRF allocation and spending over the last 10 years has been characterized by an increase in spending due to the rising frequency and severity of disasters, with notable spikes in spending due to specific catastrophic events and the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the past three decades, FEMA spent a total of $347 billion (in 2022 dollars) from the DRF to respond to disasters.

From 1992 to 2004, DRF spending averaged about $5 billion a year. However, spending has since increased to an annual average of almost $17 billion over the 2005 to 2021 period. This increase in spending has been primarily driven by supplemental appropriations for a handful of very severe disasters in the past several years. In particular, the relief efforts for hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma, all of which hit the United States in 2005, accounted for nearly 20 percent of DRF spending over the past 30 years.

In 2020 and 2021, DRF spending totaled $47 billion and $43 billion respectively, the two highest annual totals in the DRF’s history. About 75 percent of those amounts, roughly $67 billion in total, was provided for pandemic-related purposes—mainly for unemployment compensation, an uncharacteristic use of the fund.

In August 2023, the Biden Administration submitted a supplemental appropriations request to Congress that included $12 billion for the DRF to cover a projected shortfall in the fund and provide additional resources for potential forthcoming catastrophic events. This request was later increased to $16 billion. Congress passed and President Biden signed into law a continuing resolution lasting through November 17, 2023, that included the $16 billion in supplemental appropriations for the DRF.

Budget Control Act

The Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 introduced significant changes to the budgeting of the DRF. Prior to the BCA, budgeting for disasters was based on a limited five-year average spending that ignored the possibility of catastrophic years and relied on emergency supplementals in those years. This was in part because of the implementation of deficit reduction efforts in the 1980s, which made budgeted disaster assistance compete for a limited pool of discretionary budget authority in the appropriations process. The BCA mandated that more realistic annual disaster-related costs be budgeted in annual appropriations for the DRF.

The BCA introduced a system designed to cap federal spending, while also creating provisions to adjust these caps for certain high-priority expenditures. An integral feature was the “allowable adjustment” specifically for major disaster costs as designated under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act. The introduction of the disaster relief allowable adjustment meant that a more structured part of these expenses could be factored into regular appropriations, thus streamlining the process, and lessening the reliance on ad hoc supplemental bills.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) annually reviews and calculates the adjustment size based on a modified 10-year average of disaster relief appropriations. This method disregards the highest and lowest outlier years to mitigate atypical spikes or drops in funding. Notably, if the full adjustment isn’t utilized within a fiscal year, the unused amount could roll forward, but this was only true until FY2017 when any unused carryover would expire.

Despite the expiration of the BCA caps in FY2021, later budget resolutions have maintained the disaster relief adjustment mechanism, allowing certain funding to bypass spending limits, thereby perpetuating the approach established by the BCA to more realistically budget for previous disaster-related spending.

Moving Forward

Assessing the efficacy of the BCA adjustment depends on the lens through which it is viewed. If the aim was to reduce disaster-related spending, the evidence does not indicate a clear impact due to the nature of disaster relief being intrinsically tied to the scale of the disasters themselves. However, if the goal was to integrate disaster spending into the routine appropriations dialogue and curtail the need for supplemental appropriations, it has shown effectiveness.

TCS has often critiqued budgeting practices, and with respect to the BCA, we have typically been concerned with the way caps and exceptions can lead to less fiscal discipline. In principle, we support the idea of a separate disaster fund account as part of the annual budget process. History has demonstrated that while we may not know where or when disaster strikes, disasters are inevitable, and it only makes sense to budget for them.

For the DRF, the solution may lie in bolstering its funding through the regular appropriations process. The Budget Control Act of 2011’s provision for major disaster costs allowed for a smoother allocation of funds, but it hasn’t negated the need for supplemental appropriations entirely. This is in part because disaster costs are growing and the DRF budget requests are retrospective. Better forecasting future costs could lead to better budgeting, which can also lead to better decision-making on using budgeted dollars on mitigation to reduce those risks and costs. Further, by increasing the annual appropriations, the government could reduce its reliance on supplemental injections of funds. Furthermore, the ability of FEMA to direct a small portion of emergency disaster funding to mitigation efforts should be reviewed and extended.

Through this complex yet necessary reevaluation and restructuring, there’s potential not only to streamline the funding process but also to ensure that the DRF is prepared to meet the growing demands of disaster response in a fiscally responsible manner.

Get Social