To view the full report in PDF format, click here

Addressing Gas Waste on Public Lands (The 2016 BLM Waste Prevention Rule)

The BLM has a statutory duty to prevent the waste of publicly owned resources pursuant to the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) and the Mineral Leasing Act (MLA). However, as many independent reports have documented, and the recent proliferation of waste demonstrates, the agency has failed to meet these obligations. That failure was due in large part to the outdated framework governing oil and gas production on federal lands.

Notice to Lessee 4A (NTL-4A) was written in 1979 and did little to incentivize the reduction of gas waste. To address the shortcomings of NTL-4A and reduce gas waste from leaks, venting, and flaring on public lands, the BLM finalized the Waste Prevention Rule in 2016 after years of working with industry experts and other stakeholders.

The final 2016 methane waste prevention rule included comprehensive leak detection and repair (LDAR) requirements, methane capture standards for various field equipment and common drilling practices and established volumetric and percentage-based venting and flaring limits.

If fully implemented, the rule would have incentivized operators to capture and sell previously wasted gas, reducing methane emissions by over 35% and producing millions of dollars in royalty revenue for taxpayers over the next decade.

Rolling Back Public Protections for Private Gains

In early 2017, despite the urgent need to address the problem of methane waste, the BLM began efforts to repeal the 2016 rule. A draft of BLM’s new rule was released in February and finalized in September 2018. The new rule substantially revised the 2016 rule by eliminating its most significant requirements.

According to the agency’s own estimates, the new rule will result in lost royalty payments of up to $80 million, the loss of 299 Bcf of natural gas production, lost cost savings from gas that would have been captured and sold under the 2016 rule of $735 million and forgone methane emission reductions valued conservatively at $259 million.

How the States Stack Up:

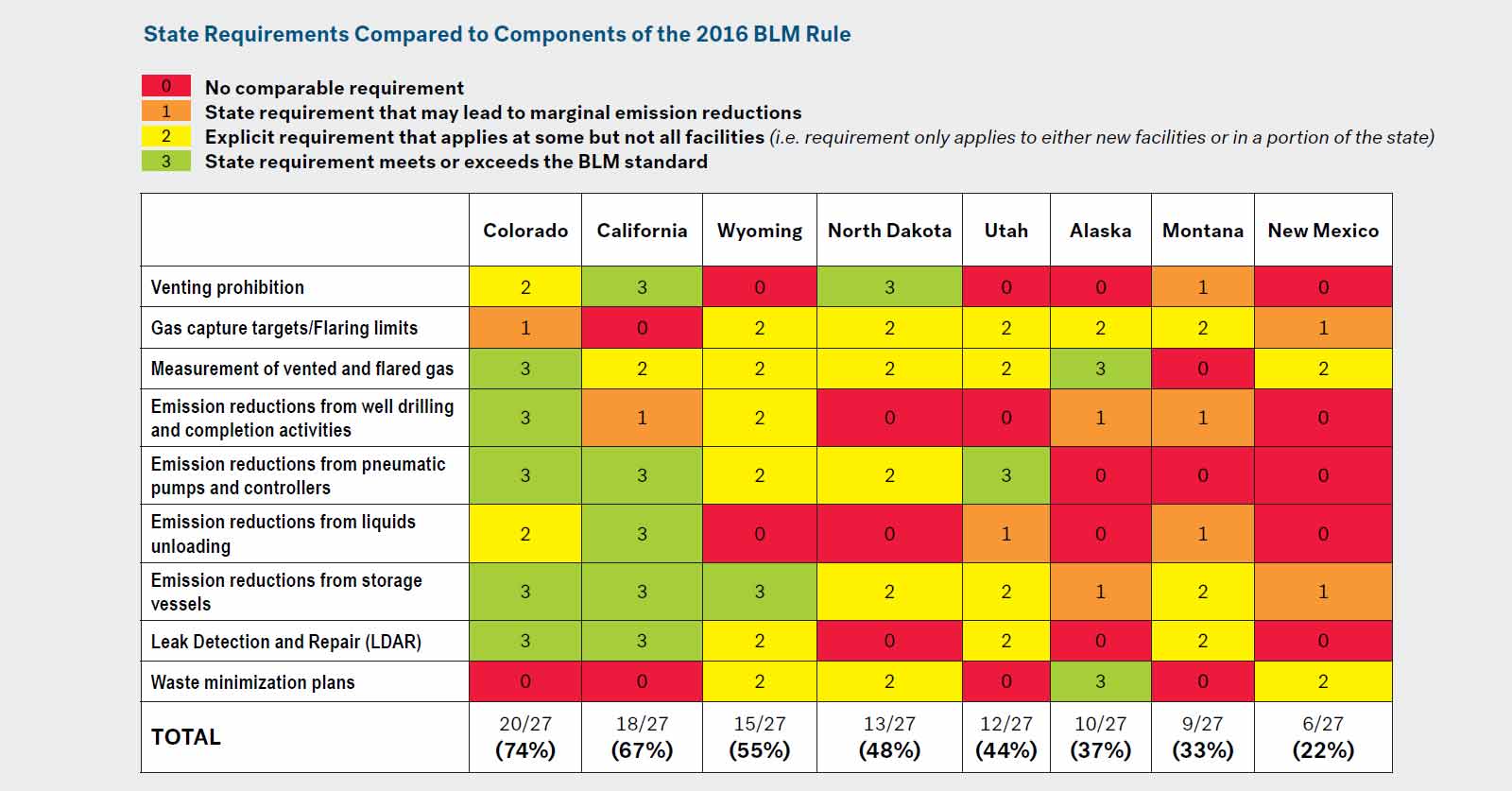

Companies developing oil and gas resources on federal lands are required to meet the standards set by the BLM, those set by the state in which they are operating, or whichever are more stringent. To reduce the extensive waste of natural gas on federal lands, the BLM’s 2016 rule set standards that were often more stringent than existing state rules. In doing so, the 2016 rule provided more consistent guidance for companies operating in different states and ensured all federal oil and gas operations were held to the same minimum standards.

Under the newly finalized rule, companies will be required to meet the state standards only. That is, the new rule relies on existing state rules to limit natural gas losses on federal lands and to determine when operators will be charged royalties for wasting gas. However, several western states have inadequate or nonexistent natural gas waste and methane reduction regulations. As a result, the impact of the new rule will vary by state.

The following eight states were selected based on the amount of federal oil and gas leasing and production occurring in each. These are the states that will be most impacted by the repeal of the 2016 BLM rule.

The table below illustrates how individual state’s requirements compare to nine significant components of the 2016 BLM rule. It highlights where states have met or exceeded the BLM standard as well as those instances where the repeal of the rule may leave emission sources unaddressed. It also allows for comparisons between state regulatory regimes.

Conclusion

States have taken wildly different approaches to minimizing natural gas waste. Some have established requirements that meet or even exceed the 2016 BLM standard while others have left significant sources completely unregulated. Relying on this patchwork approach will lead to inconsistent standards across our public lands and more importantly will result in pollution and the continued waste of taxpayer owned resources. We need consistency and continuity in the way we regulate the oil and gas industry on federal lands to minimize waste, improve public health and protect the environment. The 2016 final rule provided a common-sense and cost-effective framework for achieving these goals.

To view the full report in PDF format, click here

Requirements of the 2016 BLM Methane Rule

The 2016 final rule aimed to curb methane emissions and natural gas waste on public lands by establishing standards for operators that reduced or eliminated venting, flaring and leaks. Had it been fully implemented, it was projected to reduce methane emissions by 180,000 tons per year (tpy) (estimated to be worth up to $247 million). Moreover, the capture of previously wasted natural gas would lead to increased production of over 41Bcf per year, helping to generate additional royalty revenues of up to $14 million annually. Altogether, the 2016 final rule would reduce venting by about 35%, reduce flaring by 49% and reduce total methane emissions by 35%. For comparative purposes the requirements of the 2016 final rule are summarized below:

Venting Prohibition:

Venting is the act of intentionally releasing uncombusted natural gas to the atmosphere. Some venting is unavoidable and necessary for safety reasons. However, operators often vent gas in instances where it could be easily captured and sold or safely combusted. Under the 2016 rule, the venting of natural gas was prohibited in all but a few specific circumstances.

Gas Capture Targets/Flaring Limits:

The rule set targets for the percent of associated gas from development oil wells that an operator must capture in a given month. The capture percentage increased over time, starting at 85% and growing to 98%. The rule also established allowable flaring limits which specified the volume of gas an operator could flare without it counting towards the capture percentage. The volume limits declined annually. Over time, as capture percentages increased, and allowable flared volumes decreased the amount of gas operators could flare decreased dramatically. Additionally, the rule also stated that any gas flared or vented in excess of these requirements would be subject to royalties.

Measurement and Reporting:

Operators must measure or estimate the volume of all gas vented, flared or used on site. The BLM needs this information to evaluate compliance with the gas capture targets and flaring limits established under the rule, and to ensure the agency is properly assessing royalties. More generally, the public has a right to know how much of its gas is being wasted and this requirement goes a long way towards increasing transparency.

Drilling and Completions:

To bring a new well into production it first has to be drilled, then completed. During those operations and before the well is connected to permanent production equipment, gas will escape from the wellbore. Often this gas is vented directly to the atmosphere. However, there are a number of best practices that can be used to reduce or eliminate the need to vent gas during these events. Under the 2016 rule, operators were required to flare, capture and sell, use on site, or reinject gas produced during drilling operations and well completions.

Pneumatics:

Pneumatic controllers and pumps are automated instruments used for maintaining a process condition, such as liquid level, pressure, and temperature or for circulating fluids. Many pneumatic devices are often powered by pressurized natural gas. When pressurized gas is used, many pneumatic devices release or vent some amount of that gas. According to BLM’s own analysis, pneumatic pumps and controllers accounted for 36% of all vented federal gas in 2013. The 2016 rule required reductions in venting from pneumatic controllers and pumps. Specifically, it required devices with high bleed rates (leakage rates) to be replaced with low or no bleed devices or to route emissions to a combustion device.

Storage Vessels:

Enclosed tanks are often used to store oil, condensate, other hydrocarbon liquids, and produced water. While in the tanks, these liquids release hydrocarbons and other gases. Tanks can be pressurized and controlled to reduce the amount of gas that escapes. The 2016 rule required operators to reduce emissions from storage vessels by routing emissions to a combustion device, continuous flare or sales line.

Liquids Unloading:

Over time, liquids and solids accumulate in a wellbore, restricting the flow of gas and reducing the productivity of a well. Liquids unloading is the act of removing an accumulation of liquid hydrocarbons or water from the wellbore of a completed gas well in order to allow the gas to once again flow freely. Often the process of removing these liquids results in the release of large volumes of gas. The 2016 rule allowed venting (i.e. purging) and required operators to “consider” other methods of liquids unloading but required operators to submit justification for the use of purging and required the use of best management practices to minimize loss of gas if purging techniques were being used. The 2016 rule also required operators to report the volume of gas vented or flared from liquids unloading.

LDAR:

Under the 2016 rule, leak detection and repair (LDAR) inspections were required for all well production facilities, compressors and produced water facilities located on a federal lease. Inspections were to be conducted semi-annually for all well production facilities and quarterly for all compressors, using optical gas imaging technology or a portable analyzer. Any leaks greater than 500 parts per million (ppm) were to be repaired within 30 days. Operators were also required to submit an annual report to BLM describing their LDAR activities.

Waste Minimization Plans:

Operators were required to submit plans detailing how they would comply with the methane venting, flaring and leak requirements of the rule and how they planned to capture associated gas once a well began producing, with every Application for Permit to Drill (APD). BLM had the authority to delay the approval of an APD until a plan was submitted.

For state specific information, please see the full report

Get Social