In recognition of the 150th anniversary of the Mining Law of 1872, the Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources of the House Natural Resources Committee held a hearing on May 12 to discuss the General Mining Law of 1872. Enacted during the Grant Administration, the 1872 Mining Law still governs production of hardrock minerals on federal lands to this day. Not only has the law been giving away valuable hardrock minerals like gold, silver, and copper to mining companies for free for 150 years, it has also left taxpayers with billions of dollars of cleanup liabilities for abandoned hardrock mines.

Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Department of the Interior, Steven Feldgus, testified at the hearing. He explained the Department’s plan for the Interagency Working Group created in March to review hardrock mining permitting and oversight on Federal lands. The working group will solicit public input and include all stakeholders—tribes, taxpayers, mining companies, and mining communities because “everyone has something to gain from reform of the mining law,” said Feldgus.

The Deputy Assistant Secretary also pointed out that the mining law designed 150 years ago no longer suits the priorities and challenges of the 21st century. America needs an updated mining law to meet the growing need for responsibly sourced critical minerals to realize a clean energy economy and combat climate change, he argued

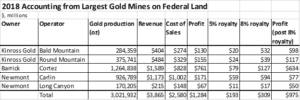

In the hearing, debate centered on the effects of imposing a gross royalty on hardrock production. Opponents of the idea claim it would make mining operations “unprofitable.” The available data suggest that’s not the case. Using revenue and production data from five gold mines located on federal lands, TCS found that a 5% royalty on gross income would have generated $193 million in 2018 and an 8% royalty would have netted taxpayers $309 million. Even after an 8% gross royalty, however, these gold mining operations would have remained extremely profitable. Gold prices have since risen to almost $1800 per troy ounce ($/oz), compared to an average of $1272/oz in 2018, which means that taxpayers have lost even more in potential revenue the last two years.

Not all mining operations are as profitable as gold, but flexibility could be incorporated into any royalty system when setting minimum royalty rates for locatable minerals. Other safeguards could also be put in place, like providing discretion for the Department of the Interior (DOI) to provide royalty relief with public notification of any rate reductions.

The mining industry advocates for a net profits (also called net proceeds) royalty, which collects a percentage of the minerals’ value after the mining companies’ costs are deducted. But a net profits royalty creates opportunities for gamesmanship when calculating deductible costs. The cumbersome accounting required for reporting and auditing net royalty payments would also increase administrative costs.

A royalty on gross income would be the most transparent and the best way to finally give taxpayers a fair return on the valuable hardrock minerals we all own. The steady stream of revenue from a hardrock royalty could also be used to reclaim abandoned hardrock mines, which are liabilities created by the mining industry.

When asked about other ways to pay for abandoned mine reclamation absent a royalty, Ms. Debra Struhsacker, Co-founder and Director of Women’s Mining Coalition, suggested Congress could appropriate the mining claim fees DOI collects for abandoned hardrock mine reclamation after covering for related administrative costs. The data we have indicate that would be infeasible. DOI collects a minimal location fee currently set at $40/claim, a one-time processing fee of $20/claim, and a maintenance fee charged to individuals or companies with 11 or more claims currently set at $165/claim, or $165/20 acres for placer claims.

According to annual budget justification documents, DOI has collected around $686 million in fees from FY2012 to FY2021. The excess of the collection after subtracting administrative costs, which is usually around $40 million per year, is around $289 million from FY2012 to FY2021.

In comparison, the Government Accountability Office estimated that federal agencies spent $2.9 billion from 2008 to 2017 to reclaim abandoned hardrock mines. The 10-year fee collection of $289 million would have been barely enough to cover just 10% of the of the 10-year reclamation costs. Without a steady stream of revenue from hardrock royalties, taxpayers will have to spend hundreds of millions of dollars per year cleaning up mines abandoned by the hardrock mining industry.

Prior to the hearing, House Natural Resources Full Committee Chair, Rep. Grijalva (D-AZ), whothe hearing, introduced H.R. 7580, the Clean Energy Minerals Reform Act of 2022. The bill would establish a permitting and leasing system for hardrock mining instead of the current claim and patent system, impose a royalty rate of 12.5% on gross value of production for new mining operations and 8% on existing operations, and create a royalty exception for small miners. The bill would also create a reclamation fee of 7 cents per ton of displaced material, which would be used to fund abandoned hardrock mine reclamation.

Just like TCS vice president Autumn Hanna said in her testimony to the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee on the Mining Law of 1872 last October, “No one thinks simply giving away valuable minerals for nothing makes fiscal sense. And no companies should be allowed to leave toxic messes on our land and avoid the tab for cleanup. Taxpayers deserve better.”

We look forward to seeing any renewed efforts on reform. For more information see our latest letter to the House and Senate and fact sheet.

Get Social