Anybody road tripping through the Corn Belt this Labor Day can’t miss the obvious signs of farm profitability. From shiny new grain bins and irrigation equipment to new homes and buildings, the riches of farmland and farmers’ bank accounts will stand out to even those who can’t tell a plow from a planter. Consecutive years of record or near-record profits in the agriculture sector have led to low levels of debt, high equity, and a surplus of cash. Now, despite a recent downturn in crop prices, these good times aren’t about to dry up. Subsidies from Uncle Sam are there to keep ‘em rolling.

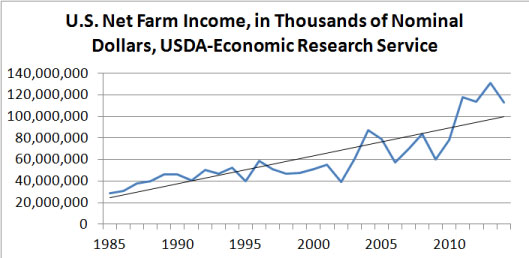

While some media chicken littles warned of doomsday scenarios if corn prices fell below $4 per bushel, which they have, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Economic Research Service (ERS) estimated Tuesday that 2014 national farm profits will nearly tie the third highest level in history. Net farm income of $113 billion, $17 billion above USDA-ERS’s February estimate, is expected to surpass both the most recent five- and ten-year averages. (See graph below). It’s a good time to be farming.

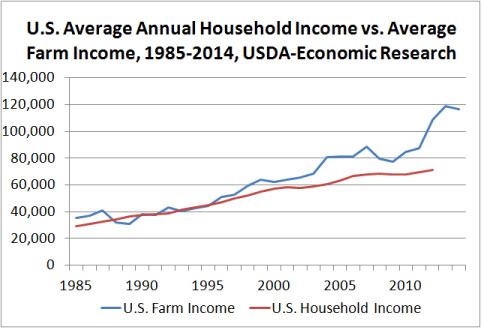

The farm economy has come a long way since 1985 when Willie Nelson and pals started Farm Aid concerts to help the hard-scrabble family farmer stay on their land. Instead of scraping by, today farm households are more likely to earn significantly higher incomes (counting both on- and off-farm income) than the average U.S. household. Farm household income is expected to reach $117,000 in 2014, a slight dip from the 2013 record of $119,000, while the average U.S. household earned a third less in 2012. (See graph below). And with much of the country suffering during the recession, states heavily reliant on agriculture barely blinked. In fact, three of the four states with the lowest unemployment rates are located in farm country – South Dakota, Nebraska, and North Dakota – with 3.7, 3.6, and 2.8 percent unemployment levels, respectively.

This unprecedented run of profitability is due in large part to an unparalleled level of taxpayer-paid supports for the big five commodity crops – corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, and rice. Through a complex web of government-set minimum prices, shallow loss income entitlement programs, highly subsidized crop insurance, ethanol mandates, and other federal subsidies, taxpayers are on the hook for providing agribusinesses a level of federal support that no other U.S. industry enjoys. And this goes way beyond any notion of a “safety net” protecting from catastrophic market collapse, severe crop losses, or weathering of unforeseen crises. New taxpayer-subsidized payouts from the 2014 farm bill, enacted in February, will kick in when farm revenue dips as little as ten percent from an expected level. Most crop insurance contracts automatically increase a farmer’s revenue guarantee when prices increase—though they don’t reduce the guarantee if prices drop. And taxpayers even pay for programs to teach farmers how to make more money off of government payments. This all makes sense when lawmakers design farm bills to, as the House Agriculture Committee Chairman Frank Lucas (R-OK) said himself, “get us through bad times and make the good times better.”

Instead of propping up well-off industries, Congress should make a farm safety net that’s more cost-effective, transparent, accountable to taxpayers, and responsive to the market and our nation’s current financial situation. With a half-trillion dollar annual budget deficit adding to a $17.7 trillion debt, taxpayers can’t afford our outdated farm supports.

Get Social