Ten billion taxpayer dollars per year in subsidies won’t fix farmers’ problems. Why? Because dollars alone won’t solve any problem. Join host Steve Ellis and TCS Senior Policy Analysts Josh Sewell and Sheila Korth for an exclusive look behind the curtain at the special interests driving the formation of the 118th Congress’ Farm Bill.

Episode 50: Transcript

Announcer:

Welcome to Budget Watchdog, All Federal, the podcast dedicated to making sense of the budget, spending and tax issues facing the nation. Cut through the partisan rhetoric and talking points for the facts about what’s being talked about, bandied about, and pushed to Washington, brought to you by Taxpayers for Common Sense. And now the host of Budget Watchdog AF, TCS President Steve Ellis.

Steve Ellis:

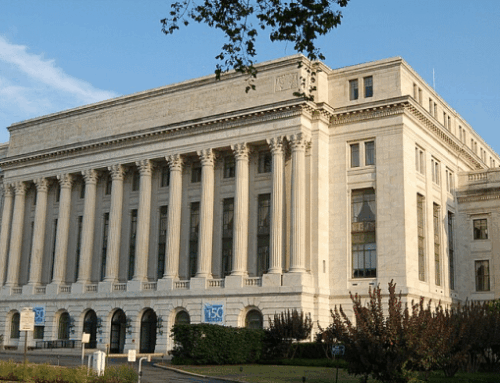

Welcome to All-American Taxpayers Seeking Common Sense. You’ve made it to the right place. For over 25 years, TCS, that’s Taxpayers for Common Sense, has served as an independent nonpartisan budget watchdog group based in Washington DC. We believe in fiscal policy for America that is based on facts. We believe in transparency and accountability because no matter where you are on the political spectrum, no one wants to see their tax dollars wasted.

Today on the podcast, we’re going “agro”. I mean, sure we’re agitated about the intransigence of policymakers when it comes to agriculture policy. You listen to this podcast. You know. Well, in the world of farm and food policy, the every five-year cumulative final exam is coming up fast, the Farm Bill, and as far as we can tell, few have done their homework and most can’t even find their textbook.

Joining me on this agro edition of the Budget Watchdog All Federal, the usual suspects, Mr. Agriculture TCS, senior policy analyst, Josh Sewell, and the Oracle of Omaha herself, TCS senior policy analyst, Sheila Korth. Ag policy avengers, assemble!

Josh Sewell:

Thanks, Steve. I feel like I wrote the book for this course, or at least I should write the book.

Sheila Korth:

Thanks, Steve. I brought my calculator too.

Steve Ellis:

Sweet. So let’s just dive right in. Sheila, record hot temperatures and drought plague much of the country and the US is really feeling the heat and so are the crops, everything from corn to wheat with hundreds of crops and livestock in between. I hear it’s a little toasty there in Omaha today?

Sheila Korth:

Yeah, I think it’s a forecasted high of 98 today with a heat index of 115. It may be even up to 120, I just read this morning.

Steve Ellis:

Yikes. Well, we definitely have the heat. We’ve got basically about the same forecast here in Washington, but the heat index, I think I saw about 110, but we haven’t had the drought. With the humidity here, we’ve gotten our share of rain and thunderstorms in the summer. Lobbyists, though, have always been keen to point out that there are lower crop prices and higher input costs as reasons why certain crop producers need more subsidies. So what’s going on there?

Sheila Korth:

Yeah, well thanks Steve. We’re actually in something like a severe drought right now. I’ll have to go back and look at the drought monitor map, but a lot of Nebraska has been in exceptional, severe, extreme drought for three years now, and it’s actually spread across the Corn Belt. There was a lot of talk about a month ago that we were going to be back in the times of the 2012 drought, which was this historic drought that cost taxpayers a lot of money through federal crop insurance subsidies and other subsidies. But there were some rains that came through in the last few weeks, but it’s back to being really hot and dry here. So if you look at the map, you’ll see that that’s going to have an impact on taxpayers’ pocketbook this year.

Steve Ellis:

Certainly. And Josh, I was talking about these, the push for more subsidies, more disaster assistance. I mean, how predictable is that, Josh?

Josh Sewell:

Well, unfortunately it’s very predictable. So I don’t want to be the cynic out of the gate, but you work on this long enough and every single year is a disaster year in agriculture, and it’s not because it’s actually a disaster. It’s because, well, it’s a fight about money, and I think that’s frankly one of the problems with the Farm Bill because there are some legitimate needs right now. Sheila just talked about some of those, but it doesn’t frankly matter what’s going on. They’re going to ask for more money.

Steve Ellis:

Isn’t there already a safety net in place? I mean, didn’t we already written in legislation ways that they’re supposed to be bailed out in these conditions.

Josh Sewell:

Yeah, and this is the biggest crux of the issue for us. We spend billions of dollars every year creating a safety net for farm businesses. And so the biggest one we should talk about is federally subsidized crop insurance. And so far that program is on pace to make $19 billion in indemnity payments and it’s going to go up more because of some places that haven’t made their claims yet for the drought. So $20 billion on just one program.

And also there’s other programs, there’s one for livestock, there’s another one for trees, there’s another one for the fruit off of the trees. There are numerous programs out there that are budgeted for that are the safety net. Yet every single year, farm lobbyists come out and say, “We need even more money because of,” insert the so-called disaster that they see.

Steve Ellis:

Well, if they’re having losses every single year versus occasionally, do we need to do, or do they need to do, something different perhaps?

Josh Sewell:

You would think so, right? We certainly advocate for things to be a little bit different. And so this is where you get to the question of are you having actual losses or are you just looking for money?

And I think that’s one of the hardest things to figure out right now is how do you build an adequate safety net that protects farmers from things they can’t protect themselves from? What is the role of the federal government and what is the role of the states and what is the role of the individual? And that’s where we’re spending most of our time fighting is figuring out what should you be protected from, what should you not and what is your personal responsibility as an individual, as a corporation, as whatever? And so yes, if you’re doing something and it’s not working, you should change.

Steve Ellis:

So Sheila, one of the things you hear about is some of these operations farming towards the program, orienting their work towards maximizing the subsidies versus really having a safety net. And then also, if you could address how some of the policy adjustments that people are talking about, adjusting certain subsidies, really pick certain winners and losers even in the ag community.

Sheila Korth:

Absolutely, Steve, we’ve seen that year in and year out, unfortunately. Just to start, when you look at which crops are even eligible for some of these subsidies, you’re really talking about corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, rice, and peanuts. And that leaves a lot of other crops out. That leaves out a lot of fruits and vegetables that people actually eat. And it also leaves out, historically, much of livestock production as well, although there are some subsidies for them. But just starting at step one, you’re already leaving a lot of folks out of the equation.

And then the subsidies to the people who do get them are huge for some producers. So a lot of producers don’t get much money each year, but some of the largest producers get a ton of money. We’re talking millions of dollars each year. The Government Accountability Office and other independent analysts have documented some of these instances of waste, fraud and abuse. And it’s both in commodity Farm Bill programs and it’s also in the Federal Crop Insurance program.

And now, given a lot more subsidies that we saw that came out during COVID and the last five years with ad hoc disaster aid, too, we’re now seeing huge payments to those large farmers coming from other programs as well. So when Josh used to talk about a subsidy sandwich, I think we’re talking about a subsidy buffet now.

Steve Ellis:

A subsidy buffet, all right. So more than just a sandwich. So Josh, it’s somewhat all about that base, right? Or all about that baseline protection, right?

Josh Sewell:

Sure. So let’s be fair. Agriculture is very diverse. We have a large country. We have, according to USDA, about 2 million farms. Honestly, half of those aren’t actually farms that you and I would think of farms. Those are folks who are retired and use that as some sort of off-farm income or it’s a lifestyle choice, and it’s not my determination of that. It’s USDA. They call them hobby farms. It’s a hobby farm or it’s a retirement farms, but of the million farms that are out there, it’s extremely diverse. It’s hard to create a safety net for everybody.

But so much of what’s going on in DC right now, it’s not the committees and interest groups and folks like us coming up and saying, “What’s the best safety net we can design for this diverse agriculture?” It’s special interest coming and saying, “We spent X amount of dollars last year. How can we get at least that much and more this year?”

Because it’s called what we call a baseline protection bill. So the baseline, it’s determined by the Congressional Budget Office and it affects all these mandatory programs. Any sort of mandatory program, whether it’s in agriculture or in Social Security or in Medicare, Medicaid, these big entitlement programs, you are entitled to the benefits of those programs if you meet the criteria. So, especially when they’re permanently authorized or even if they’re only technically authorized for a few years, like farm programs, there’s a set amount of money that we can expect to spend.

That amount of money over 10 years creates the baseline so that when you make a new farm, bill, the CBO will analyze that, all the programs in that bill. Anything that goes up or anything that goes down in expected spending, you have to meet the baseline. If you spend more, you’re going to have to find revenue. If you spend less, you have savings. And now that fight about exactly how you push on one program and pull on another to maintain within that baseline is what they’re fighting about now. So oftentimes you’ll see it’s about money. It’s not about policy.

Steve Ellis:

Right. I mean, I remember a couple Farm Bills ago, there was when they finally got rid of direct payments, which were really tied to the 1996 Freedom to Farm, which is basically giving farmers cash on history of what they farmed before when they got rid of the direct payments because they were really indefensible. They made sure they found other programs to plow that cash into. So they didn’t actually lose that from the Farm Bill. Right?

Josh Sewell:

Exactly. And that issue is probably what got me the most interested and perhaps upset, is that the right word, with farm policy is that when I engaged in that issue, it was everybody pretty much agreed. We shouldn’t do that as policy anymore, paying farmers, or technically people who own farmland and are supposed to be farming it. You didn’t have to be a farmer. There’s a lot of money that went to people who just own land that weren’t farming it under direct payments.

Doing that no matter what is egregious, especially when, during that time, agriculture had some of its most profitable years. So giving people money just because they have something, that’s not a safety net. That’s not market oriented. That’s not like SNAP program. That’s not like unemployment where you get it when you need it. It’s a social safety net program that just gives money all the time.

That’s not something we normally do, especially the conservatives we work with. When Sheila and I go to these offices, let’s be frank, we say, “What do we need? What programs do you guys actually need?” And we can put that into place and then we figure out what they cost. That’s what we should be doing. But they’re not doing that. They’re saying, “We had $5 billion in direct payments. How can we make sure we get 5 billion next year in these new programs?”

Well, that’s not how we evaluate most programs. It just doesn’t make sense to me that, oh, it’s a safety net program. It doesn’t work unless we get money. A safety net is supposed to be there to catch you, right?

Sheila Korth:

Well, I think as a taxpayer group, we would say that that $5 billion per year needed to go to deficit reduction. It just needed to be eliminated. But you’re right, Steve, they did plow that into other programs. And now, unfortunately, we have seen those programs balloon in cost. And as I mentioned before, other subsidies layered on top in that what Josh used to refer to as a subsidy sandwich.

But it’s actually gotten worse. Just one example is direct payments used to be $40,000 per year per individual, and we are now up to $125,000 per year per individual. And there’s a whole bunch of loopholes within that to allow farmers and those who own farmland and other non-farmers to reap those increased subsidies. And then there’s a whole bunch of other subsidies layered on top. So we’ve actually gotten to a place where this is much worse for taxpayers and not benefiting farmers either.

Steve Ellis:

Right. And we’ll get into what I’m about to talk about a little bit more later, but Senator Grassley has talked about how many of the people who are getting these subsidies are more familiar with desk chairs than they are with tractor seats. But we’ll talk about Senator Grassley in a bit. I want to go towards what do we need to see that policymakers need to do? So Josh, let’s talk about the three Fs.

Josh Sewell:

Yeah, this is a simple way to think of farm policy, and honestly I think most safety net programs, is follow the three Fs, focused, fiscally responsible and foster resilience instead of dependence. It’s pretty simple.

Focused basically means only pay for things that we need to pay for and only give benefits to people who truly need those benefits. Fiscally responsible should be common sense. Again, it’s you’re only spending money that you have to spend and spend it in a way that’s efficient. And then fostering resilience means programs that are safety net programs. A safety net program is supposed to be there on hard times. When you need it, you get insurance. I don’t know anybody who goes every year and says, “Man, I wish I would’ve got a payment under my car insurance,” because the only way you get that is if you get hail damage or someone runs into you.

But the way the lobbyists evaluate crop insurance and some of these other programs is if they don’t get money, they consider it a failure. That’s the opposite of a safety net. And so it’s indicative that some of these programs, our friends at EWG, the Environmental Working Group, did a report and they found that there were nearly 20,000 individuals or corporations that received a commodity payment every single year, 38 years in a row. If you’re getting a “safety net payment” 38 years in a row, that’s not a safety net. That’s a subsidy or a bailout. And we’re not even talking crop insurance. That’s the other programs.

Steve Ellis:

Right. I mean, that’s a hammock. It’s not a safety net. I’m stealing somebody else’s line from that, but I’ll do that. So Sheila, what are you hearing from farmers about the subsidies?

Sheila Korth:

You know, Steve, I have not talked to one farmer who says that they want more subsidies ever. I’ve talked to a lot of farmers, and a diverse set of farmers, but what we hear in Washington DC is something completely different than what farmers are actually saying. The farm lobby is saying, “We need more money. We need increased reference prices,” known as price loss coverage, which is essentially the government coming in and saying that we’re going to have a minimum price for certain crops. I think Josh called it Soviet style at one point, but it is a lot of government intervention into the marketplace, and it’s not encouraging farmers to plant for the market. It’s encouraging them to plant for which subsidies they’re going to receive.

So in 2020, when we were in the middle of the pandemic, we actually saw a record amount of farm subsidies go out to the agricultural sector, nearly $50 billion, and that’s not even counting crop insurance subsidies. So we’re talking more than $50 billion in one year.

And again, those direct payments that some of these subsidies were supposed to replace were only $5 billion a year, so we’re really getting to a point where there’s an excessive amount of taxpayer subsidies going out the door from Washington, going to people who don’t even need them or want them.

And I think another point there is to look at who’s going to benefit. So you had asked that earlier, Steve, about which crops are going to benefit or who benefits from the subsidies. When you’re looking at where the drought is and where the extreme heat has been already this summer, the subsidies that are being proposed right now would actually go to producers in the South who have not been experiencing some of the same conditions that we’re feeling here in places like Nebraska. So I think there’s a real disconnect coming from Washington.

Josh Sewell:

Let’s be clear, then. I think there’s also a disconnect. It’s not just when we talk to the farmers, when we get that chance. The interest groups aren’t always on the same page, and we will speak with anybody who invites us to talk. And was it a week or two ago, I went and spoke with the corn growers, and to be frank, the National Corn Growers, there’s some things we agree with them. There’s a lot of things we disagree, but in our conversation, they made it clear that their number one priority is to maintain crop insurance.

Now, their definition of maintaining crop insurance, we have some problems with, but the very least, they are not, at least when they speak to us, and even sometimes in their official correspondence, they are not in favor of taking crop insurance and then layering on this price loss coverage and this arc and some other program and a margin protection. So there are reasonable people, even at some of these organizations that you might think that we don’t agree with.

And it’s happened at other interest groups as well that we’ve spoken to, other folks who are representing commodity interests. But I think it really gets to the point that there is a fear amongst certain lobbyists that if you actually had to compete, if your farmers had to actually go out and be good business people, there are certain areas where it’s clear we should not be farming the way we are farming. And the only reason that continues is because we are, in fact, bailing those individual producers out.

And it’s a hard conversation we need to start having because we can’t afford to do every single thing we want and maintain every single farmer farming the way he or she has in the past. It’s just we can’t afford it even if we want to do it. And we shouldn’t want to do that either.

Steve Ellis:

Right. I mean even you don’t even have to think about climate change. There’s different climates, different soil types, different issues in different parts of the country. And so clearly you can’t grow everything or whatever you want, wherever you want, and just provide a subsidy for it.

You’re listening to Budget Watchdog, All Federal, the podcast dedicated to making sense of the budget, spending and tax issues facing the nation. I’m your host, Steve Ellis, and we continue going agro now with TCS senior policy analysts, Sheila Korth and Josh Sewell.

So Sheila and Josh, we’ve been doing this a long time. Taxpayers for Common Sense has been around since 1995. We worked on every single Farm Bill during that time. I’ve been involved in every single Farm Bill in that time and have the scars to show for it. But who’s been in the trenches with us on this? Who are some of our champions on the hill and what in particular are they pushing for?

Josh Sewell:

Well, one of our biggest champions on the Hill is actually Senator Grassley, Republican from Iowa. We’ve also done a lot of work with Mr. Blumenauer, a Democrat out of Oregon. He’s been around since, I guess, since before TCS was around actually, on the Hill. And also right now, Senator Shaheen, a Democrat from New Hampshire. So that’s our current members. And we also have a lot of work with other folks on both sides of the aisle on smaller issues or as they come out of the fold, as the Farm Bill comes closer.

So it’s interesting that our champions for these common sense changes that we want to see in farm policy come from literally every corner of the country. We have them in traditional ice states, the corn bean part of the country, we have them in the west, and we have them in specialty crop areas, and we have them in places that are heavy on dairy.

Steve Ellis:

So Sheila, what are some of the things that this diverse group of politicians are pushing for? What are some of the issues that they’re plugging in on that we’re supporting them?

Sheila Korth:

Right. Well, just this week, senator Chuck Grassley from Iowa introduced a longstanding bill or set a reform that he’s championed for a very long time. And that is rocket science, apparently, to say that those receiving farm subsidies should actually be farmers. So we don’t think that’s rocket science, but apparently you have to spend time writing a bill to say that because Senator Grassley has successfully pushed similar reforms, in addition to reigning in some egregious subsidies, in the past.

But unfortunately, when those proposals then, or those requirements, get sent to the US Department of Agriculture to actually be implemented to ensure that there’s not waste, fraud and abuse in farm subsidy programs, they get watered down. So Senator Grassley is back at it, trying to ensure that those receiving farm subsidies are actually working on the farm for a certain number of hours each year.

Josh Sewell:

And let’s be clear. Under Mr. Grassley’s legislation, you can still manage a farm. You don’t only have to physically till the soil. You don’t have to get oxen and stand behind them, or you don’t have to just drive a tractor. You can be involved in the management decisions in those farms, but it can’t just be management only. And it can’t be fake management, because what we have seen in the past is it’s called farming by FaceTime.

You literally never step foot on the farm. You don’t actually make major decisions. You just call into a conference call once or twice a year and make a planting decision or decide which inputs to buy, so which fertilizer from Acme or from Acme Inc. Which fertilizer company do you buy from? It’s not integral to the operation of the farm. And let’s be clear about this too, that there are certain regions of the country and certain types of farming where they create these farms that are paper farms, basically.

You have all these managers, you have all these people who are working on it, not because you need those people, because you’re farming the program. You can grow corn and beans on 10,000 acres with a handful of folks, or you can grow corn and beans on 10,000 acres with 32 managers. It depends on how you set up your farm.

And so this is not about getting more efficient farms. It’s about getting people to capture cash. And again, one of the studies that we saw in the past was looking at not even the main farm programs, but just looking at the trade war bailouts. There was a farm that got more than $2.3 million in the trade war bailout program. There was a payment limit in that program. It was $125,000. Well, the way the farm operation got more is it had 32 managers. It doesn’t make any sense. Help farmers. You don’t need to help people who are simply sitting at a desk, like myself could be one day, and are invested in a farm and have decided to just continue that nice side hustle.

Steve Ellis:

Preach brother. All right, so Sheila, back to you. There’s a few other pieces of legislation that are out there that we’re supporting, right?

Sheila Korth:

Yeah. There’s been another bill introduced in years past that would reign in crop insurance subsidies because they are currently unlimited. Taxpayers don’t know where the money is going, and there’s no cap on income. So you can literally be a millionaire or a billionaire and still receive unlimited taxpayer subsidies. And I’m not joking. So Senator Shaheen Bill and Representative Blumenauer have introduced legislation in the past to reign in some of those subsidies in different ways, but it’s mind-boggling and it’s not helping farmers in the long run.

Steve Ellis:

And there’s also some legislation that we’ve supported that also… We’re not just talking about crop insurance, also looking at better targeting conservation dollars, right?

Josh Sewell:

Yeah, definitely. It’s called the Equip Reform Bill, and that’s actually in the Senate. It’s supported by Senators Lee from Utah, a Republican member, and then Senator Booker from New Jersey. Very different states, very different ideologies, but the idea behind that program would be it would basically say the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, which is supposed to be a program to provide public benefits for various resource concerns, including water quality, water quantity, and importantly, mitigating the effects of climate, is that it would prioritize those practices which USDA and farmers themselves say are the best at combating climate change, and give more money for those and less money for things that aren’t have a good climate impact, like building fences or building roads, which you can technically get under this program, which is also a little bit mind-boggling that a conservation program will pay for road construction.

But the idea is that you’re going to be spending our dollars in a way that has more impact and is more effective for us as taxpayers, as well as the farmers themselves.

Steve Ellis:

Sheila, we had some of your neighbors on, so to speak, I’m using that term loosely. They are fellow Nebraskans. We had them on the podcast earlier this year. And for the benefit of Budget Watchdog AF listeners that may be not recalling exactly what they were talking about, what did Scott and Skyles, the father and son farmers, talk about?

Sheila Korth:

Yeah, Steve, earlier this year we had a podcast entitled Farm Bill Field Trip where we interviewed farmers Scott and Skyles Kincaid, who farm in northeast Nebraska, mainly corn and soybeans, but they’ve tried some other diversified crops in the past as well and cover crops. And Scott believes, and has believed for a long time, that farmers would be better off without farm subsidies. And this is coming from someone who has been in three years of straight drought. And he believes that because Scott has said that eliminating unnecessary subsidies would actually benefit rural communities and beginning farmers. Here’s what Scott had to say,

Scott Kincaid:

People are expanding their operations significantly at the expense of rural communities. Obviously it doesn’t take as many people to farm an acre as it used to. I farm several more acres than my grandparents did. That’s just technology and progress and there’s nothing wrong with that. But when you have farmers who are working the system to get thousands of dollars from the government that they can use to expand their operation, then you’re displacing people who could have been farming that now they can’t afford to because these big farmers are driving up the price of rent, so they push them off the farm.

Well, what happens to rural communities, the hardware store and lumberyard and the schools? It makes it harder. You don’t have as many fire departments and on down the line. And like I said, part of that is just technology, but a lot of it, in this case, was not technology. It was government more or less picking and choosing the winners and the losers. And that to me was what I felt was wrong.

And that’s what I think about my grandparents. They didn’t bid up the price of land because they couldn’t afford to lose that. So it didn’t happen. Now you got the government guaranteeing that you’re not going to go broke. So yeah, let’s go buy more and pay more. And to me, that doesn’t seem really good for rural America because it’s killing towns and communities.

Steve Ellis:

Wow, that’s really impressive, coming from somebody who’s would stand to benefit from some of these subsidies, at least you would think so. And it really does say that there’s this disconnect between some of the lobbying operations and their representatives, and the lawmakers and how they’re portraying this and how they try to say what farmers actually want or need.

Josh Sewell:

And Scott and Skyles aren’t the only people who’ve said that to us. They’re the only two that have been on a podcast so far, but they won’t be the last. That’s where we try to work for is like we’re not here just to have an arbitrary number of savings. We’re not trying to eliminate programs just to get a scalp on our wall. We want to figure out what do we need to do to help agriculture be successful? What do we need to do to help people get a fair shake in this environment?

And once you get out into the country and you start talking to folks, we’ve seen it in Illinois, we’ve seen it in Nebraska, members from the south have talked to us about this. Even that rectangle of death and despair that is Kansas, when I go out there, you can talk to those folks and they’re reasonable, it turns out, once you start talking to them for a while.

And so this isn’t as hard as it has to be. We make it harder here in Congress because we’re only fighting about dollars. I want more money next year than I had last year. There’s not a lot of room to talk about what do we really need to do, and importantly, what can we afford to do now because we’re $32.5 trillion dollars in debt. We can’t continue the same path we’ve had in any part of the budget.

Steve Ellis:

Just like to remind you, Josh, my dad is from Kansas. Now granted he left and joined the Navy, but still. So I don’t view Kansas, and many of our listeners probably don’t view Kansas, quite the same way as somebody from the state of Missouri, or state of misery, does.

Josh Sewell:

State of misery. You come up with that on your own, Steve?

Steve Ellis:

Let’s just say I’ve heard it here somewhere before. So September 30th is not just the end of the fiscal year, it’s also the end of the last Farm Bill. And so it expires. You’ll hear a lot of doom and gloom right about going back to depression era or post-depression era policy. So what happens as we get closer? I mean, congress has left town. They’re not coming back until mid-September. So what’s going to happen here on the Farm Bill?

Josh Sewell:

Well, I can tell you one thing. We don’t have time to write a good Farm Bill before it expires. So step back, take some breathing room and realize that the last two Farm Bills, the one passed in 2018, and then before that was 2014, as we were fighting about those Farm Bills, the Farm Bills expired both years and the world didn’t collapse on October 1st. So the reality is in the nuts and bolts of the bureaucracy, nothing happens for a few months and ultimately nothing happens really until January 1st. So we have breathing room.

If you need to extend it for a year, you can. Congress did that the last two times we did a Farm Bill. They extended it for a whole year while they got the details done. So let’s take some breathing room, ignore the rhetoric, and figure out what we truly need to do and what we can afford to do. And we have the fall to do that. And honestly, we have another year if we need to. And I think it’s better to get a good Farm Bill than to get a quick Farm Bill.

Steve Ellis:

Sheila, you were out in the wilds of the country when the Farm Bill expired. Did you see hellfire and brimstone? Was it the end of times? Cats and dogs living together? What did you see?

Sheila Korth:

It’s amazing, the rhetoric from Washington, and my favorite actually Steve, is when Congress marks up a Farm Bill and writes a Farm Bill at the same time it’s right in the middle of planting season out here in farm country. So to have farmers actually be able to constructively engage in that debate is non-existent because they’re working 20 hours a day or something crazy. So that’s always one of my asks. Josh said, we need to do a Farm Bill, take our time in writing a good Farm Bill. I think we need a common sense Farm Bill, and I think we also need one that is going to provide, or the timing at least, is going to provide farmers adequate time to voice their opinions.

Steve Ellis:

Well, and this isn’t the end of this Congress. I mean, it is the first session and they’re in until next year. So they certainly have time in this Congress to write a better Farm Bill than they’ve done in the past. And so we’re going to hold them to that. Sheila Korth and Josh Sewell, thank you for harvesting the facts with me on the podcast today.

Josh Sewell:

Always a pleasure.

Sheila Korth:

Thanks, Steve.

Steve Ellis:

Well, there you have it, podcast listeners. It’s a song and dance we’ve heard before, 10 to 20 billion or more in taxpayer dollars per year in subsidies is not enough to fix farmers’ problems, or at least the politicians representing farmers’ problems. Well, if this episode has taught you anything, let it be this. Dollars alone won’t solve any problem.

This is the frequency. Mark it on your dial. Subscribe and share and know this. Taxpayers for Common Sense has your back, America. We read the bills, monitor the earmarks, and highlight those wasteful programs that poorly spend our money and shift long-term risk to taxpayers. We’ll be back with a new episode soon. I hope you’ll meet us right here to learn more.