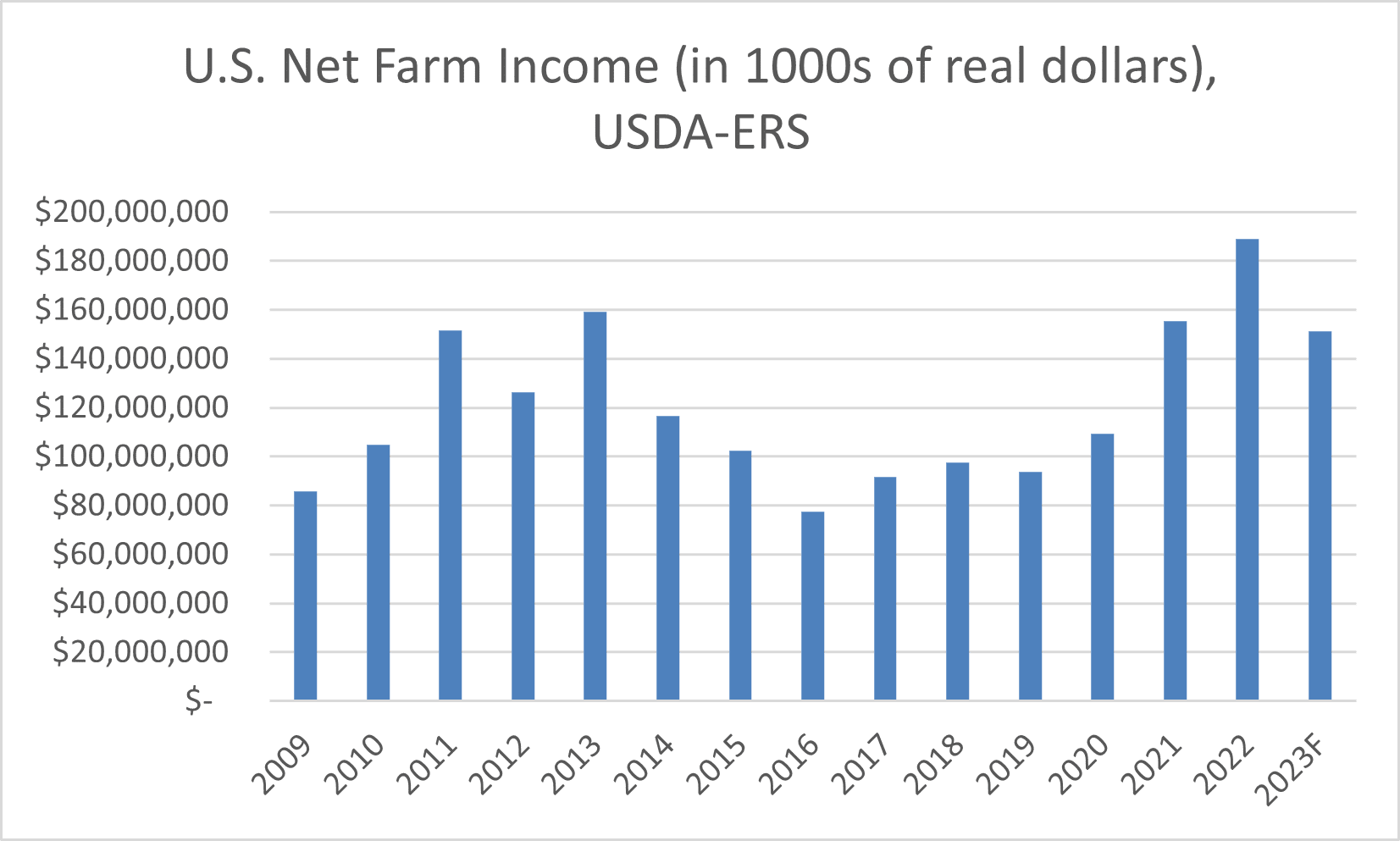

Today, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Economic Research Service (ERS) reported that net farm income in the U.S. set a new record of $189 billion in 2022, and 2023 net farm income is expected to reach the 5th highest level in a half century ($151 billion). Despite evidence of a healthy farm economy, certain agribusiness lobbyists are calling on Members of Congress to drastically expand farm subsidies in the next farm bill.

Adding to our nation’s $34 trillion debt to expand the already generous taxpayer subsidy smorgasbord for certain producers is a bad idea – for taxpayers, farmers, rural communities, and the climate. Here’s a few reasons why:

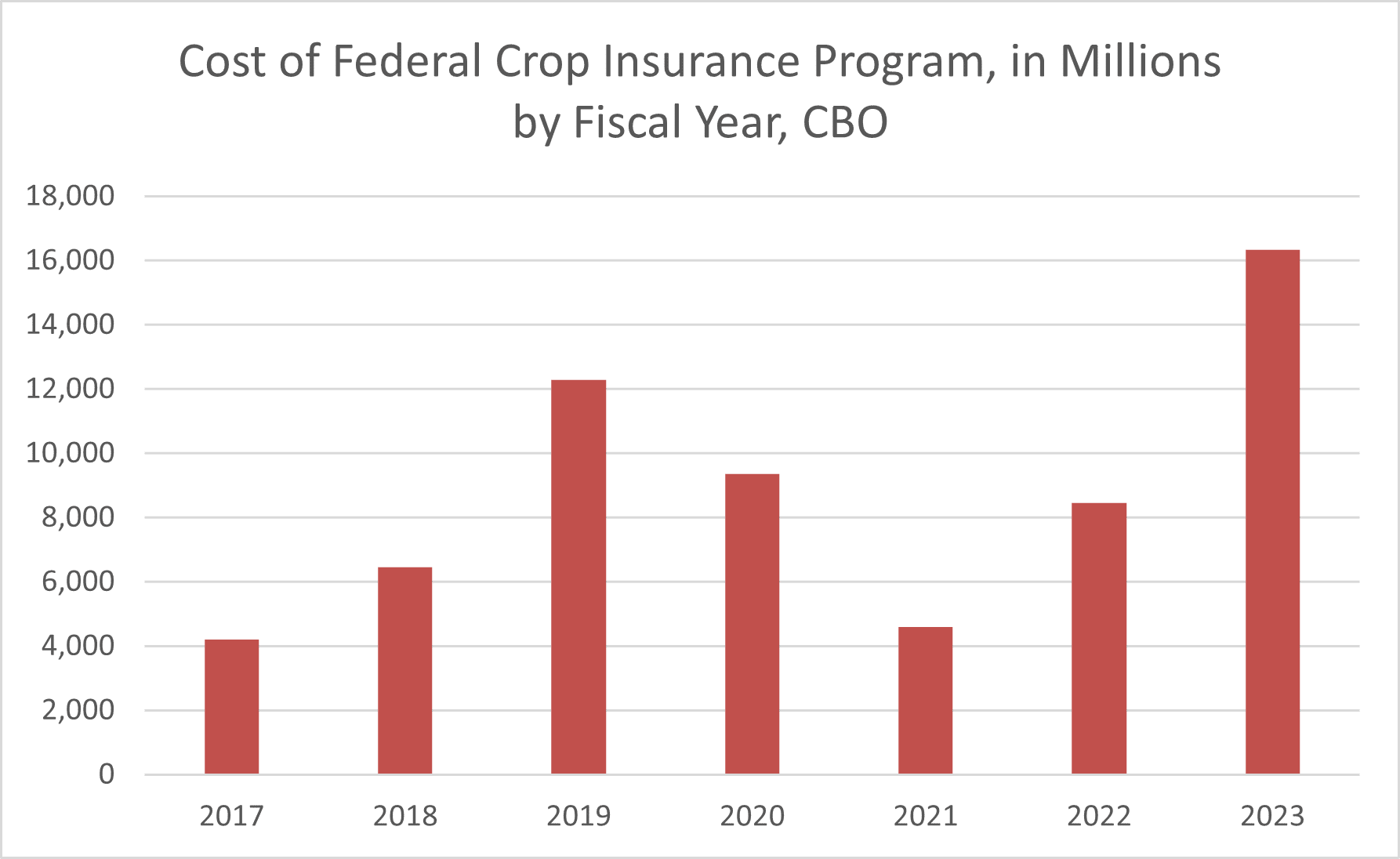

1. Federal taxpayers already provide a smorgasbord of subsidy programs for certain crops focused on price declines (Price Loss Coverage, or PLC), small dips in income (Agriculture Risk Coverage), and highly subsidized crop insurance. Together, these duplicative programs are expected to cost taxpayers nearly $150 billion over the next decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). USDA-ERS expects direct government payments to agriculture (primarily through PLC, ARC, and unbudgeted disaster aid) to total $12 billion in 2023, with $12 billion in crop insurance premium subsidies and other taxpayer subsidies layered on top.

2. Farmers and rural communities would be better off without current subsidies propping up the incomes of large and already wealthy agribusinesses. A University of NE-Lincoln study found that federally subsidized crop insurance contributes to farm consolidation and depopulation of rural communities. Most farm subsidies flow to the largest and wealthiest landowners and agribusinesses, with the Government Accountability Office (GAO) finding that unlimited federal crop insurance subsidies even benefit millionaires and billionaires. Subsidies flowing to medium- and small-scale producers, beginning farmers, and diversified producers are either nonexistent or significantly lower.

3. Farm subsidies contributed to the loss of carbon-rich grasslands, wetlands, and other sensitive land, according to USDA-ERS. These losses affected wildlife habitat, soil and water quality, long-term resilience, and much more.

Certain agribusiness lobbyists cite higher input prices, such as those for fertilizer, when calling for higher government-enforced reference prices (PLC subsidies) in the next farm bill. However, today’s USDA-ERS update shows that costs for manufactured inputs are expected to decline by 14% from 2022 to 2023. Meanwhile, the value of crop production is expected to drop by a much lower amount – only 5%. Regardless of how you slice it, the bottom line is still the same – as a whole, farmers are expected to continue to be profitable in 2023.

Increasing government-enforced reference prices in the next farm bill won’t come at no cost to taxpayers. In fact, some estimate the subsidy expansion – which props up minimum prices for crops like peanuts and rice – could cost taxpayers tens of billions. Cutting agricultural conservation investments (enacted in the Inflation Reduction Act) to pay for unnecessary subsidy expansions would be a major step in the wrong direction. Instead, Congress should focus on eliminating barriers farmers face when investing in measures to help their businesses become more resilient to drought, heat domes, floods, and more.

There couldn’t be a better time to pare back wasteful subsidies . Creating a federal farm safety net that is focused, fiscally responsible, and fosters resilience – instead of dependence on taxpayers – will benefit our nation’s fiscal outlook and the future of agriculture.

* Please note that the 2022 net farm income figure of $189 billion is in inflation-adjusted (real) dollars.

Get Social