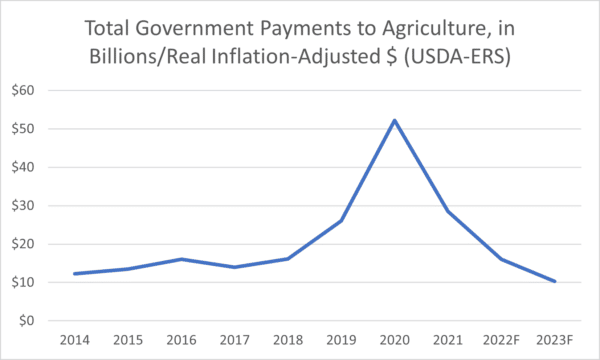

Government payments to agriculture are expected to decrease to $10.3 billion this year, down from $16 billion in 2022 and even higher levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. These projections are from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). Farm income subsidies in 2023 are expected to fall to $6 billion, with an additional $4 billion directed to farm businesses participating in agricultural conservation programs.

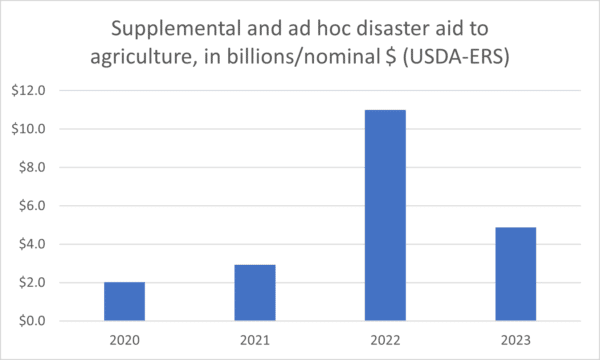

Approximately half of the $10.3 billion expected to flow from taxpayers to the agricultural sector will come from supplemental and ad hoc disaster aid. The taxpayer cost of unbudgeted disaster aid, arising from Congressional appropriations in response to recent hurricanes, wildfires, drought, and floods, has risen significantly over the past handful of years. These funds are separate from and in addition to taxpayer spending directed by farm bill safety net programs.

Two other important points, which happen to cover the following farm bill titles and topics the Senate Agriculture Committee will address in a hearing this Thursday, include:

(1) Title I Commodity Subsidies: USDA-ERS expects farm commodity subsidies, which historically cost taxpayers approximately $5 billion annually, to reach just $69 million in 2023. That’s down from more than $6 billion in 2020. With these farm bill subsidies tied in whole or in part to crop prices, USDA-ERS expects higher crop prices this year to negate the need for taxpayers to fork over subsidy payments tied to low prices. Government-set minimum crop prices are known as Price Loss Coverage (PLC) and the other primary commodity program – Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) – subsidizes small dips in certain agricultural producers’ expected income each year.

(2) Title XI Crop Insurance Subsidies: USDA-ERS projections for total government payments to agriculture in 2023 do not include federally subsidized crop insurance, which the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected, as of last August, to cost taxpayers an additional $8-9 billion on average each year. USDA-ERS does, however, expect federal crop insurance indemnities to reach near-record levels in 2023 ($18.55 billion), meaning the combination of relatively higher crop prices plus drought still affecting major crop-producing regions of the US will increase payouts arising from the taxpayer-subsidized program. CBO will release updated budget and economic projections, including revised projected costs for federally subsidized crop insurance, on February 15th.

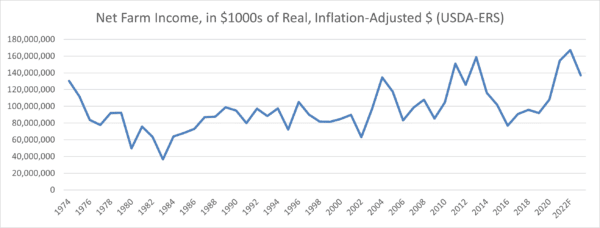

Meanwhile, net farm income for the agriculture sector as a whole is projected at $136.9 billion in 2023. While the value of agricultural production is expected to drop slightly from last year’s near-record level, recent through-the-roof input costs are expected to decline slightly, providing a bit of relief for farmers facing high fertilizer, pesticide, and other expenses. If realized, 2023 net farm income, a measure of overall farm profitability, will be significantly higher than the 10-year average ($22.8 billion higher to be precise, in real, inflation-adjusted dollars), and the fifth-highest level (again, inflation-adjusted) since 1973.

Hence, asks from the farm lobby for more taxpayer subsidies in the 2023 farm bill should be rejected in favor of smart investments and policy changes that can help agricultural producers build resilience to future economic and climate challenges, instead of increasing certain producers’ dependence on taxpayer subsidies.

The 2023 farm bill debate is in full swing, with Senate and House Agriculture Committee hearings being held across the country. The time is now for common sense reforms to farm subsidy programs that for too long have wasted taxpayer dollars on duplicative payments, subsidies to millionaires and billionaires, and policies hurting instead of helping rural communities and beginning farmers. Taxpayers and farmers alike deserve a farm safety net that is focused on true need, fiscally responsible, and fosters resilience.

Get Social