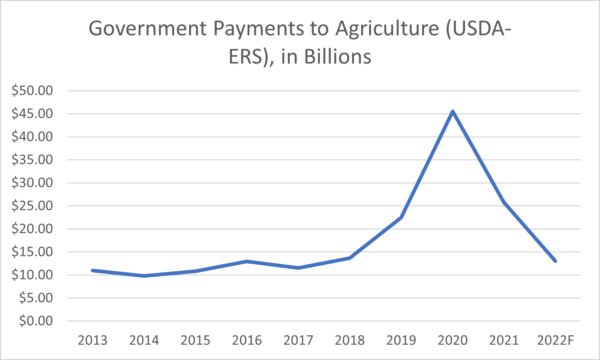

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government stepped up taxpayer support for the agriculture sector with tens of billions of dollars in ad hoc aid. Government payments to agriculture reached a record high – $46 billion – in 2020, according to the US Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). USDA-ERS projects 2022 farm subsidies will decline to $13 billion, closer to historic averages, but ad hoc and supplemental disaster aid payments are still expected to remain high.

Speaking of high, net farm income. Despite rising input costs for everything from fertilizer to fuel, 2022 net farm income is still expected to reach $147.7 billion, down slightly from the 2021 level of $148.6 billion (in inflation-adjusted dollars). If realized, net farm income (after expenses are subtracted) would be the second highest level in the past decade and the third best year for the sector as a whole since 2000.

Government payments are expected to comprise 8.8 percent of net farm income in 2022, down from nearly 50 percent in 2020 (the second highest level on record) due to the influx of COVID-19 aid to the agriculture sector.

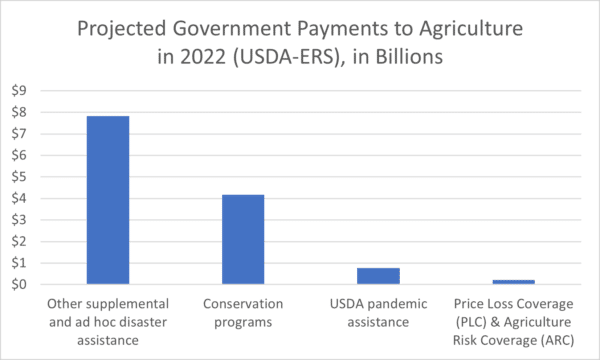

Interestingly, less than two percent ($214 million) of government payments in 2022 are expected to be derived from farm commodity programs, including Price Loss Coverage (PLC) and Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) subsidy payments. These farm bill programs subsidize certain commodity crop producers when prices or revenue decline, but with current crop prices higher than recent averages, subsidy payments are expected to drop in 2022. If realized, this year will be a great example of a healthy farm sector as a whole even without billions of dollars in commodity crop subsidies that historically weigh down taxpayers’ pocketbooks (and many farmers say they don’t need). Some farm groups are lobbying for expanded subsidies in the next farm bill even though taxpayers already subsidize certain ag producers’ revenue, profit margins, crop prices, and yield dips through various federal programs.

Supplemental and ad hoc disaster aid, primarily tied to recent droughts, floods, hurricanes, wildfires, heat domes, etc., is expected to cost taxpayers nearly $8 billion in 2022. This cost, if realized, would blow past disaster aid costs of $2.2 billion and $3.1 billion in 2020 and 2021, respectively, with $0 in years prior. Spending $8 billion in one year would rival the taxpayer cost of the federal crop insurance program, which subsidizes similar – and sometimes duplicative – losses. (Please note that the taxpayer cost of crop insurance is not included in the USDA-ERS analysis above. In addition, the $1.5 billion in “emergency” agricultural disaster aid the administration recently requested as part of a fiscal year-end spending package, is also not included in the ERS estimate).

The primary difference between disaster aid and crop insurance is the taxpayer share of the benefit. Taxpayers subsidize 100 percent of ad hoc disaster aid, while the taxpayer share of federal crop insurance premiums is approximately 60 cents for every $1 of insurance coverage. Agricultural producers have skin in the game with crop insurance, covering the other 40 cents, on average. Recent conversations with agricultural producers in the Midwest have shown that farmers support the latter program – crop insurance – where they have skin in the game, as opposed to ad hoc bailouts. Federally subsidized crop insurance was expanded over the last few decades as a means of getting Congress out of the business of appropriating unbudgeted, post-hoc disaster aid.

USDA-ERS projections, however, show farm supports are headed in the wrong direction with increased reliance on disaster aid. The farm safety net should promote resilience, instead of dependence on federal subsidies. Ad hoc disaster aid does little, if anything, to prepare individual farmers and ranchers or the agriculture sector for the economic and climate challenges lying ahead. Ad hoc payments routinely arrive years after the event for which they were supposed to assist and do not come with technical assistance to aid farmers in adapting their operations to better withstand the peril that caused the loss. In addition, providing duplicative subsidies to producers fails to spend taxpayer dollars wisely or invest in cost-effective risk management solutions that help producers in the long run.

Congress and USDA directed $16 billion in ad hoc disaster aid spending to agriculture, for disasters experienced in 2017 and later years. USDA-ERS estimates that just $3 billion of this total will remain after 2022. Congress has its work cut out for itself next year, to develop a more cost-effective, transparent, and accountable farm safety net that is responsive to actual need, instead of political will.