Tim Velde says he would rather have free trade than more checks from the government.

“I don’t know a single person out here farming that wouldn’t rather get their money from selling crop,” said Velde, who grows corn and soybeans near Hanley Falls, Minn.

But this year, farmers have received more federal money than ever: more than $40 billion.

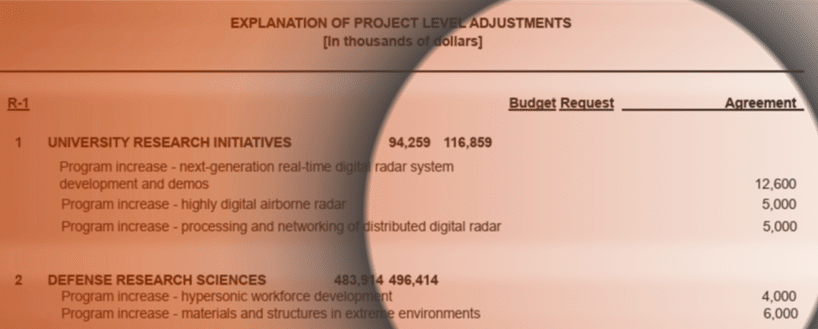

Such assistance to farmers has risen throughout the presidency of Donald Trump, shaped mainly as compensation for sales to China farmers lost after that country retaliated in a trade war begun by the U.S. in 2018. Last year, farmers received $30 billion from the government. Trump approved more aid this year because of the pandemic, helping drive farm income to the highest level since 2013.

With the latest round of checks announced by Trump last month, more than 40% of farm income could be from the government, the highest proportion in 20 years, the University of Missouri’s Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute estimates.

Farmers, who as a group disproportionately vote Republican and support Trump, are uneasy with being seen as on the dole.

“I don’t know any farmers that actually want to receive government aid or payments. We don’t want that,” said Brent Fuchs, a corn and soybean farmer who also raises some cows near Dundas, Minn.

But it can be difficult to find voices critical of farm subsidies, which in normal times consist largely of the ethanol mandate and taxpayer-paid crop insurance premiums. While fiscal conservatives are generally skeptical, Republicans and Democrats both champion them.

U.S. Senate candidate Jason Lewis voiced opposition to government support for farmers in the past, and was criticized for it by Sen. Tina Smith’s campaign in recent months. But he downplayed those comments in his race against Smith this year.

Josh Sewell, an analyst at Taxpayers for Common Sense, said he is skeptical that these historic levels of subsidy for farming will simply go away after the pandemic and permanent resolution on trade with China.

“Once you start subsidizing people 30%, 40% of their income, it gets harder to turn them back over to the market where there’s downside risk,” Sewell said.

Aid programs have been “layered on top of each other,” he said, and seem disproportionately to be going to those farmers with the most political clout — corn, cotton, soybeans and cattle. Small farmers who sell produce at farmers markets, for instance, have received none of the aid.

“Some commodities Uncle Sam is very generous to, and others not,” Sewell said. “Disaster aid is supposed to help people survive a disaster.”

Farm income has trended lower for half a decade, as crop prices were squeezed by an overabundance of corn and soybeans. Income this year will rise, but according to the data compiled at the University of Missouri, the growth in income will come entirely from the government and lower farm expenses.

Conditions for farmers have begun to improve in recent months, thanks to renewed Chinese purchases of corn and soybeans. Corn prices are up by a third since early August. Soybean prices are up by a fifth over the same period.

Seth Meyer, who tracks farm income and subsidies for the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute and teaches at the University of Missouri, said consolidation is always happening in agriculture. More of it may have happened without the generous government payments, he said.

“If you had a bad year, this keeps you from going out of business just because you have a bad year, but it’s not going to keep you from going out of business if you are a bad farmer,” Meyer said. “Some of those people, you have just delayed the day of reckoning.”

Farmers want the money, Meyer said, but a dollar from the government doesn’t reduce a farmer’s stress as much as a dollar from the market.

The aid to farmers, despite their discomfort with it, has been a lifeline for many, Fuchs said. In addition to the trade war, farmers have faced headwinds from poor weather in 2019, their own overproduction, a strong U.S. dollar that discouraged exports and now a pandemic that has wreaked havoc on the way food is processed and sold.

“The help was basically necessary to keep most guys afloat,” Fuchs said. “There’s been a lot of things out of our control over the last few years with weather events, with trade wars.”

The trade war has been necessary, Fuchs said, and he views the recent grain purchases by China as a sign that Trump’s hard line on trade is paying off.

Velde, who was busy combining corn before the snow hit, sees it differently. Trump’s trade policy and the waivers granted to the oil industry were, in his view, manufactured problems that backed up the grain markets.

“If all that had gone to market — been shipped to China and been made into ethanol — our crop prices now would be in a good profitable area,” Velde said. “But now we’ve still got this burdensome supply of crop that we have to work through before we ever get back to a profitable level.”

Velde said the field in front of him was bent over from the straight-line winds that passed through the Midwest in the summer.

“Thank goodness for auto-steer. Otherwise we’d have no idea where we were,” he said. “Life without challenges would be boring.”

Even with those challenges, he said, “Who wants to be dependent on government for everything? It just feels wrong.”

Get Social