The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office in January forecast rising debt for the rest of President Donald Trump’s presidency and beyond. Yet, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin claimed that before COVID-19 hit, the U.S. was experiencing “extraordinary” economic growth that “would pay down the debt over time.”

Treasury officials say the claim is based on Trump’s proposed fiscal year 2021 budget, submitted in early February, which claims to put the federal budget “on a path to a balanced budget in 15 years.”

But that budget assumes economic growth that far exceeds consensus forecasts, including the CBO’s. It also assumes the significant spending cuts in Trump’s budget will be enacted by Congress. In his annual budget proposals, Trump has regularly called for slashing federal spending, only to wind up signing federal budgets from Congress that increase spending.

On “Fox News Sunday” on Sept. 6, chief political anchor Bret Baier asked Mnuchin about the ballooning national debt during the pandemic, and whether the Trump administration would address it if Trump were reelected. (The public debt has increased by about $6.4 trillion, or 44%, under Trump, rising from $14.4 billion to $20.8 billion. In August, the CBO reported that the federal deficit was $2.8 trillion in the first 10 months of fiscal year 2020, which began Oct. 1, 2019, largely stemming from spending bills in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.)

“I would, Bret,” Mnuchin said of addressing debt in a second Trump term. “I think before we got into COVID, I thought the debt was very manageable. We were having extraordinary growth. We were creating growth that would pay down the debt over time.”

CBO contradicts that projection.

A March CBO analysis of the president’s proposed budget — in which CBO did not account for the “rapidly evolving public health emergency related to the novel coronavirus” — concluded that debt will grow for the foreseeable future even if Trump’s budget were enacted. And debt is projected to grow relative to the economy as well. (We should also caution, as we often do, that any president’s budget proposal is largely a symbolic statement of priorities, not legislation on which Congress would vote.)

“GDP did grow faster than previously expected in 2018 and to some extent 2019 – and some of this is probably attributable to the tax cuts,” Marc Goldwein, senior vice president and senior policy director at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, told us via email. “But even over that period, debt grew relative to the economy. And under CBO’s latest pre-COVID projections in March, debt was projected to continue rising. CBO projected debt would grow from 79 percent of GDP by the end of 2019 to 96 percent by the end of 2030. Over that period, they projected nominal debt would rise by almost $12 trillion. In no year was debt projected to grow by less than $1 trillion year over year.”

So how does Mnuchin justify his claim?

Although the administration’s proposed budget did not show a balanced budget within the 10-year window included in its summary tables, it stated that the proposed budget would put “the Federal Government on a path to a balanced budget in 15 years.” And, a Treasury official noted, the budget suggests the debt-to-GDP ratio would fall annually in the shorter term.

“With the GDP growth we were realizing plus the path to budget balance, the debt to GDP ratio was going to start falling,” the Treasury official told us via email.

The official pointed to the administration’s Mid-Session Review, released in July 2019, that projected deficits as a percentage of GDP would steadily decline each year, and by the end of the decade, would dip under 1%. That document projected real GDP growth in 2019 to be 3.2% on a fourth-quarter-over-fourth-quarter basis, “before edging down to a sustainable 2.8 percent in the long run.”

Not only did the real GDP not grow that much by that measure in 2019 — it was 2.3% not 3.2% — the administration’s long-run projection for GDP growth is far rosier than most independent budget analysts’.

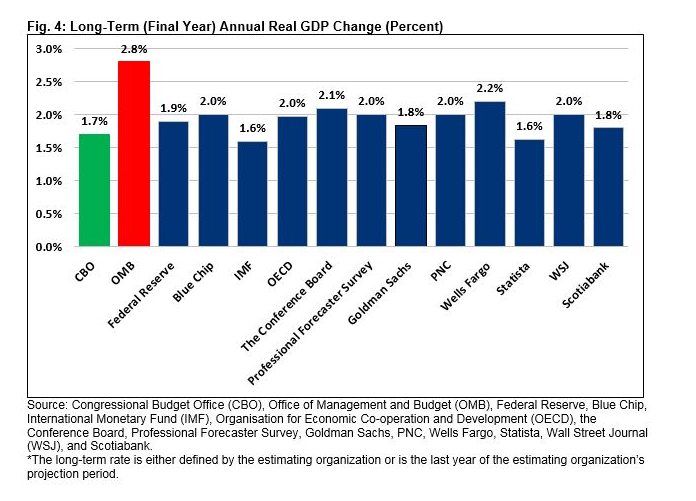

According to the CRFB, the president’s budget “relies on overly optimistic economic growth assumptions.” CBO estimated pre-COVID-19 that real GDP growth will average 1.7% over the next decade, while the White House’s Office of Management and Budget assumed an average of 2.9%.

In addition to CBO, the Federal Reserve and other independent forecasters predicted more modest GDP growth than the White House relied on to make its 15-year balanced budget projection. The CRFB provided this comparison of projections for GDP growth over the next decade (the White House projection is the one marked OMB):

Rosy Projections

The Treasury official told us: “All that has to happen for the debt:GDP ratio to decline over time is that nominal GDP growth exceed growth in debt.” If Mnuchin “thinks real growth can exceed 2% regularly and inflation 2%, then nominal growth is 4% (obviously our forecasts are better than that). So for the Secretary’s statement to be true, we have to keep deficits below that level, which the pre-COVID MSR [Mid-Session Review] did.”

But again, the administration’s forecast that the budget was on a path to be balanced by 2035 assumed long-run GDP growth to be 2.8%. And, as we said, CBO forecasts it will be below the 2% threshold the Treasury official said is needed to see the debt-to-GDP ratio decline.

Moreover, Mnuchin’s claim, and the projections in the president’s proposed budget, assumes all of the cuts proposed in that budget plan would be fully enacted by Congress. As it has in the past, the administration’s FY2021 budget proposal called for deep domestic spending cuts including to Health and Human Services, the Environmental Protection Agency, Housing and Urban Development and the State Department. But Congress writes the budgets, and the president has routinely signed budgets that increase domestic spending — undercutting the goal of pushing toward a balanced budget.

Alexander Arnon, senior analyst at the Penn Wharton Budget Model, also took issue with Mnuchin’s claim that the U.S. was experiencing “extraordinary growth” prior to the pandemic.

Pre-pandemic economic growth was strong, Arnon said. But the growth between 2018 and 2019 was waning. Annual GDP growth dropped from 3.0% in 2018 to 2.2% in 2019.

That drop was in line with expectations, Arnon said. The 2018 GDP was goosed up a bit by the tax cuts enacted by Trump, he said, but in 2019 there was less room for the economy to grow.

“I would not characterize the growth as extraordinary,” pre-COVID-19, Arnon said.

Pre-COVID-19, the Penn Wharton Budget Model forecast even more modest long-term annual GDP growth (over 10 years) than the CBO, closer to 1.6%. While that may be below some other forecasts, Arnon said, “There is no reasonable projection for the federal budget and the U.S. economy that would lead to declining debt in the foreseeable future.”

“Secretary Mnuchin must be hoping that today’s dire fiscal situation masks the very bad fiscal situation and future our country was facing pre-pandemic,” Steve Ellis, president of Taxpayers for Common Sense, told us via email. “The 2017 tax cut and the budget deals in 2018 and 2019 brought us trillion-dollar deficits in a time of relative prosperity. That profligate approach put the nation in a difficult situation to address a legitimate crisis like the current situation. Secretary Mnuchin can spin it however he wants, but at the end of the longest economic expansion in our country’s history, the U.S. was piling on debt at an unsustainable rate that easily outpaced growth.”

Mnuchin’s claim about “extraordinary” economic growth pre-pandemic that was on course to “pay down the debt over time,” relies first on the unlikely premise that Congress would fully enact Trump’s proposals to dramatically cut domestic spending, and second on forecasts of economic growth that are far more optimistic than the CBO’s and most other budget analysts’. But even if one makes those assumptions, the budget wouldn’t balance — let alone start paying down the national debt — for another 15 years.

Get Social