FEMA and other federal agencies have stopped tagging spending associated with individual storms far earlier than in the past, making it much more difficult to track contract outlays for a single hurricane across agencies.

Inaccurate totals could allow Congress and the administration to cherry pick numbers to under- or overestimate disaster spending and make it harder to plan for future disasters.

“We have no idea how much money is being spent on federal contracts to support disaster response,” Marie Mak, assistant director at the Government Accountability Office said in an interview.

“I think that’s part of the reason why we’re having all these debates,” Mak said in reference to the $19 billion bipartisan disaster aid funding package (H.R. 2157)that passed the Senate May 23 but has stalled in the House. “And if we don’t have facts and numbers out there, it makes it that much harder to know what was spent for what.”

Mak led the writing of an April report on the issue. In it, the GAO recommended the government fill in the missing contract data, but the Department of Homeland Security said that would be burdensome and impractical.

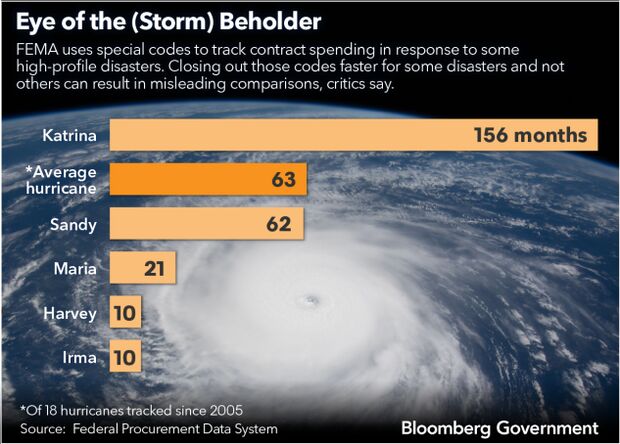

FEMA uses contract tracking codes, known as National Interest Action codes, to keep tabs on contracts intended for disaster relief in certain limited cases. NIA codes have been assigned to 18 hurricanes and a handful of other high-profile national emergency events since the early 2000s. The codes don’t track post-disaster grants distributed to state and local governments, which make up a significant portion of recovery spending, but they are the only way for the public to see how much the federal government has spent across agencies for things like construction and emergency food and water.

The average time those codes are left open for use is 63 months, according to a Bloomberg Government analysis. While the code for Hurricane Maria remain in use 21 months after it ravaged Puerto Rico, the tracking codes for the other two mega-storms that hit Texas and Florida in 2017, Harvey and Irma, were discontinued after only 10 months.

This makes the gap between spending totals for Maria and the other 2017 storms appear larger than the GAO says it actually is at the same time President Donald Trump continues to claim Puerto Rico received billions more in aid than the department’s records indicate. Contract spending for Hurricane Harvey and Irma through the end of June 2018 when their codes were closed out totaled $1.6 billion and $1.2 billion, respectively, while Hurricane Maria’s total continues to climb, at $5.8 billion, according to a Bloomberg Government contracts analysis.

Missing: $400 Million

But at least $400 million in contract spending was not captured in the coded totals for Harvey and Irma, according to an analysis done by Mak’s team. Mak said that estimate was “very low,” as only about a third of 2017 hurricane contracts with NIA codes filled out a description field with something that may indicate a connection to a disaster.

“They closed it so early when we know there’s a lot of other agencies putting contracts out in support of those two hurricanes,” Mak said.

The contract spending dispute echoes the whirl of hazy claims being made by politicians as they attempt to hammer out the disaster funding package that has been stalled since last fall, primarily over the debate over more aid for Puerto Rico. In an April 2 tweet, Trump claimed Puerto Rico had received $91 billion for Hurricane Maria. But figures from his own administration show as of March, about $42 billion in disaster funding had been promised to the island, with only $12.6 billion actually spent.

Trump’s tweet referenced an estimated cost of Puerto Rico’s long-term recovery, a senior administration official said in an email.

‘No Good Reason’

To be sure, contract spending is still tracked by each agency, even if it’s no longer readily available to the public. The Department of Homeland Security has defended the coding change. In its response to the GAO, the department said retroactively filling in the data was “not practical and places an unreasonable burden on the same disaster contracting workforce responsible for new time critical disaster contracts.” The department also said it couldn’t force other agencies to retroactively fill in their data.

Brian Kamoie, associate administrator for mission support at FEMA, told the House Homeland Security Committee May 9 it was his understanding DHS was planning to revisit those code-closing protocols to “make sure that we’re providing the transparency we need.”

Still, the DHS has told GAO it did not plan to reopen the already-closed codes for 2017 hurricanes, saying contracting has decreased. It has also already closed the codes for 2018 hurricanes, and the code for Maria is set to expire June 15.

“We felt like the reasons that DHS provided didn’t make a lot of sense to us,” Mak said, adding that contracting officers had to retroactively fill in data in 2005 for Hurricane Katrina.

A former FEMA Deputy Administrator, Tim Manning, also criticized the change. Manning served eight years in the Obama administration.

“There’s no good reason to not track the entire expenditure of public money in disaster response and recovery,” Manning said in an interview. It takes many years for disaster contracting to taper off across government, he said.

Shovel Out Funding

The code policy will continue to be scrutinized by the House Homeland Security Committee, Chairman Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.) said in an interview. Republicans on the committee, such as Dan Crenshaw (Texas) and Peter King (N.Y.) also questioned the timing of the code closures.

“Why would one want to push out anything other than accurate data?” Thompson said.

There is already a lack of accountability and oversight for where taxpayer dollars go in disaster recovery, and the codes should be re-opened to help boost transparency, Steve Ellis, vice president of Taxpayers for Common Sense, said.

“This rush to shovel out the funding, or in this case also to close out the books, gives you an incomplete picture that can lead to waste,” he said.