At some point in the midst of a messy situation, you end up thinking: How did I get here? The deficit and debt hole Washington finds itself in had many causes, but one of the enablers was the broken budget process. If lawmakers can refrain from trying to score political points, there may be an opening to reform the system so it’s harder to break, bend, and evade the rules en route to budget-busting excess.

In a positive step, last week House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan teamed up with the committee’s ranking Democrat, Chris Van Hollen, to introduce a quasi-line item veto for the President. While not a solution to our budgetary woes, this “enhanced rescission authority” would fast-track the President’s ability to submit specific cuts to Congress by requiring up or down votes on the proposals..

The joint legislation was part of a flurry of legislative proposals in recent months to remake the budgeting system. But the hard reality is that there is no one solution to our budget woes, and mechanisms are only as good as enforcement. When it comes to budgeting, Congress makes the rules, and they can agree to break the rules. But there are several process changes that will make it harder to game the system and make the budget decisions and information more transparent.

Currently, budgeting relies on a ten-year window. So phasing in expensive policy proposals – whether it is a large tax cut or new entitlement – so that the full cost isn’t realized until year eleven or later makes the proposals appear cheaper on the books than they are in reality. Lawmakers and the President should have to budget beyond the ten-year window, in some cases far beyond. For instance, policymakers should be able to get credit for changes to entitlement programs that protect today’s recipients and phase in twenty or more years from now. That would provide incentives to put the programs on solid fiscal footing. Congress should also be denied budget gimmicks like fake emergency spending, moving spending around temporally to evade scoring, and counting fake cuts as saving.

The budget must be made more transparent. Agencies should make the materials that undergird their budget proposals (budget justification documents) available to the public. All revenues already earmarked for mandatory spending should be documented, because while big ticket items like Medicare and Social Security taxes or gas taxes are known, many other so-called offsetting receipts fly under the budget radar on auto-pilot.

Oversight is a lost art on Capitol Hill. Many special interest programs and tax breaks survive with little scrutiny or evaluation. The first step Congress should take to fix this problem is to use the systems in place for oversight, but there are other reforms worth considering. Congress could require programs be reviewed periodically or be reauthorized regularly to retain federal funding.

Other fundamental revisions to the process should be considered and debated. Right now in the Schoolhouse Rock version of budgeting, the President submits a budget proposal in February, the House adopts their budget resolution, the Senate theirs, and they hammer out an agreement between the two chambers. This agreement doesn’t go to the President, and doesn’t have the force of law. Instead lawmakers could adopt a resolution which would require the President’s signature and at least gain agreement between the House, Senate, and President on top-line spending levels early in the year, which would set the stage for a more efficient appropriations process. Further, biennial budgeting – where in odd years a two-year budget resolution is adopted, and even years oversight is conducted – should be evaluated.

There are many more rule changes that will be debated, but at the end of the day, the rules are only as good as the people who are enforcing them. Congress can adopt all the best budgeting practices, but if taxpayers don’t hold them accountable when they try to fudge the numbers, then process reform won’t lead to progress on the deficit.

###

TCS Quote of the Week

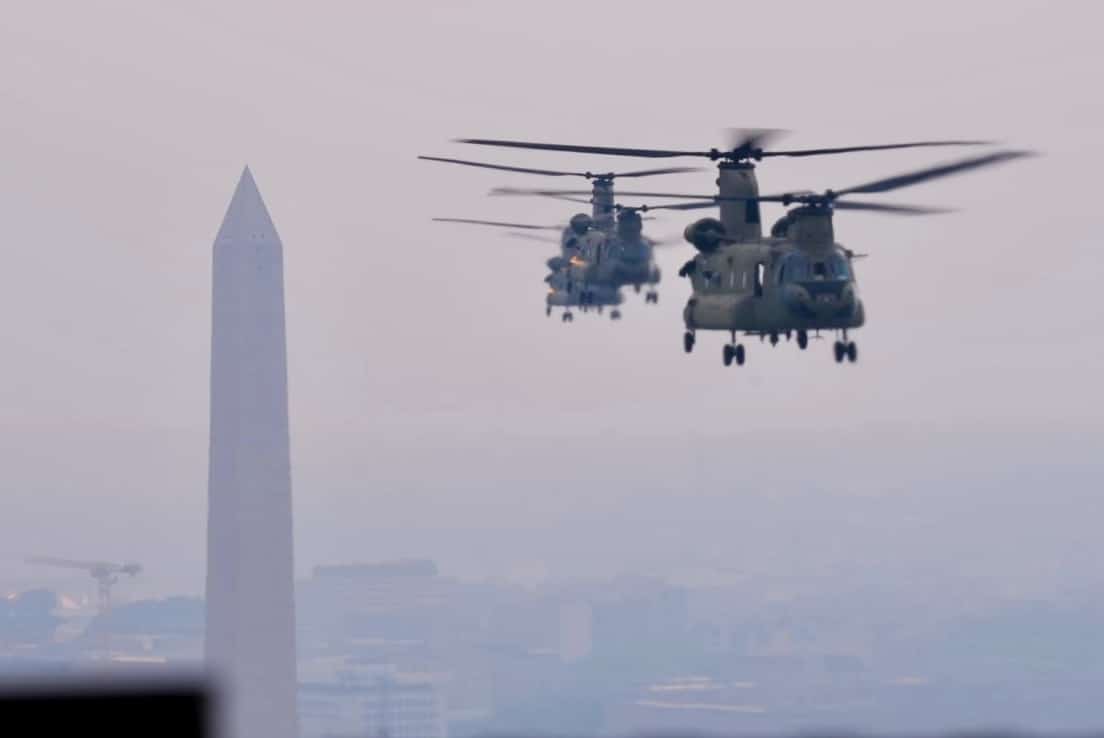

“The Joint Strike Fighter program has been both a scandal and a tragedy…[W]e are saddled with a program has little to show for itself after 10 years and $56 billion in taxpayer investment that has produced less than 20 test and operational aircraft.” — Ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee John McCain (R-Ariz.) (The Hill)